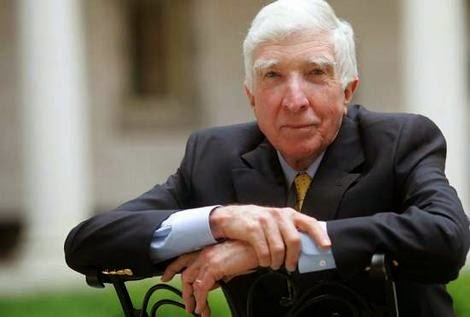

John Updike (1932-2009)

Writer John Updike's works are known for their

subtle depiction of American middle-class life. His popular Rabbit series earned him two Pulitzer prizes.

John Hoyer Updike was an American writer, poet,

literary critic and novelist. He was born on 18th March 1932 in Reading,

Pennsylvania. Updike was the only child of Wesley Russell Updike, a mathematics

teacher and an aspiring writer Linda Grace Hoyer. His mother’s writing passion

became a major influence on young John. He often used to recall his mother’s

writing desk, the typewriter and clean sheets of paper. One day he hoped to

have it all. Updike went to Shillington High School and graduated as a

valedictorian and class president in 1950. He then enrolled into Harvard where

he gained the reputation of a prolific writer being a regular contributor and

president of the ‘Harvard Lampoon’. He graduated in 1954 ‘summa cum laude’ with

a degree in English.

Updike’s initial desire was to become a cartoonist. To

pursue this goal he entered the ‘The Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Arts’ at

the University of Oxford. After completing school he returned to America where

began to contribute to ‘The New Yorker’ at a regular basis marking the beginning of a remarkable writing career.

His first story for this magazine was called ‘Friends from

Philadelphia’. John Updike

remained at his post of staff writer for ‘The New Yorker’ for two years. He wrote the columns ‘Talk of the Town’, poetry and short

stories for the magazine. Some of these stories became the groundwork for his

later poetry books such as ‘The Carpentered Hen’ (1958) and ‘The Same Door’

(1959). His 1968 novel, ‘Couples’ created a great hype by portraying the

relationship of young married couples and the complications in their lives.

Though Updike’s work in general was highly respected,

his outstanding career as a poet was distinguished with successful volumes of

poems such as ‘Telephone Poles and Other Poems’ (1963), ‘Midpoint’ (1969) and

‘Tossing and Turning’ (1977) which is considered to be one of his best works.

Updike also went through a deep spiritual crisis which he overcame by reading

the works of the theologians Karl Barth and Søren Kierkegaard. This religious

journey also influenced many of his books.

John Updike was popular for many of his previous books

but he rose to great eminence with his novel ‘Rabbit Run’ that was published in

1960. This book gave birth to one of the most famed American characters of the

20th century; Harry (Rabbit) Angstrom. His story starts in high school where he

was appreciated as a terrific basketball player. The events that unfold bring

him to a dead end job at the age of 26 and he had given up on life. Following

his name he does what he does best; he runs. Updike’s skill as a writer should

be credited here because a character so unlikable ends up gaining sympathy from

the public. The other three novels of the series are a continuation of Rabbit’s

life story. They are ‘Rabbit Redux’ (1971), ‘Rabbit is Rich’ (1981) and ‘Rabbit

at Rest’ (1990). ‘Rabbit is Rich’ won him the ‘Pulitzer Prize’ in 1982.

At 32 years of age, John Updike became the youngest

person to get elected to the ‘National Institute of Arts and Letters’. George

H. W Bush presented him with the ‘National medal of Art’ in 1989 and the

‘National Medal for the Humanities’ by G.W Bush in 2003. This great writer of

English literature died on 27th January 2009 in Beverly Farms, Massachusetts.

Interview with John

Updike

| From the National Book Foundation Archives |

John Updike, a two-time Winner of the National Book Award for Fiction -- for his novels The Centaur (1964) and Rabbit Is Rich (1982) -- and a six-time Finalist for the prize, is the author of 46 books of fiction, criticism, plays, essays and poetry. After graduating from high school in Shillington, Pennsylvania, he attended Harvard University on a scholarship, graduating summa cum laude in 1954. He then studied painting at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Arts at Oxford University before accepting a position at The New Yorker, which has published his work ever since.

Rabbit Is Rich is the third novel in Updike's highly acclaimed "Rabbit" tetralogy; in addition to winning the National Book Award, it earned the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics' Circle Award. Like all the "Rabbit" novels, Rabbit Is Richreveals the novelist's abiding interest in chronicling the terrors and pleasures of sex, marriage, adultery, parenthood and religion that ordinary Americans have experienced over the past 30 years. The tetralogy is widely regarded as Updike's best work to date, since the novels provide, as Anthony Quinton noted in a London Times review, "the fullest scope to his remarkable gifts as an observer and describer. What they amount to is a social and, so to speak, emotional history of the United States."

How is it that you decided to become a writer?

My mother wanted to be a writer, and from earliest childhood on I saw her at the typewriter; and though my main passion as a child was drawing, I suppose the idea of being a writer was planted in my head.

Who are some of the writers who have shaped your voice?

Of course, everything you read of any merit at all in some way contributes to your knowledge of how to write, but my first literary passion was James Thurber. He showed me an American voice and a willingness to be funny. I think I first became aware of his work when I was around eleven, and I actually would save up pennies to go buy the new Thurber; he was my idol until about the age of eighteen or nineteen. I wrote him a fan letter at the age of twelve and he sent me a drawing, which I've carried with me, framed, everywhere I've gone since. In college there were Shakespeare and Dostoevsky, to name two, and the short stories of J.D. Salinger really opened my eyes as to how you can weave fiction out of a set of events that seem almost unconnected, or very lightly connected.

Directly out of college, in my attempt to continue my education, I began to read Proust in an English translation by Scott Moncrieff, and the length of those sentences, and the qualities of the perceptions he was searching for, the expansive, delicious lunges into philosophy, all seemed very magical to me. At about the same period I also began to read an English novelist called Henry Green, who is semi-forgotten but for me is really a master of the voice in fiction. Rabbit is Rich is a long way from those years, but the pick-and-roll of it, the quickness of it, was written with Green's touch in mind. And, of course, behind all those interior monologues stands Ulysses; the interior monlogues of both Molly and Leopold Bloom were for me a very liberating, very exciting new way to touch the texture of human experience. But Joyce is in the air you breathe, whereas Proust and Green and Salinger stick in my mind as really having moved me a step up, as it were, toward knowing how to handle my own material.

You said once, in speaking about Rabbit, Run, that you began the novel with an interest in dramatizing a kind of scared, dodgy approach to life. What was it about that approach to life that you found so compelling?

I suppose I could observe, looking around me at American society in 1959, a number of scared and dodgy men -- and I felt a certain fright and dodginess within myself. This kind of man who won't hold still, who won't make a commitment, who won't quite pull his load in society, became "Harry Angstrom." I imagined him as a former basketball player. As a high school student I saw a lot of basketball and even played a certain amount myself, so the grandeur of being a high school basketball star was very much on my mind as an observed fact of American life. You have this athletic ability, this tallness, this feeling of having been in some ways a marvelous human being up to the age of eighteen, and then everything afterwards runs downhill. In that way he accumulated characteristics -- even his nickname, "Rabbit". Rabbits are dodgy, rabbits are sexy, rabbits are nervous, rabbits like grass and vegetables. I had an image of him that was fairly accessible, and his neural responses, his conversational responses, always seemed to come very readily to me, maybe because they were in many ways quite like my own.

Perhaps I haven't read enough novels, but I can't think of one besidesRabbit is Rich that focuses on a father and son in conflict, and is told from the father's point of view.

I suppose it is fairly unusual. Most novels are told from the young man's point of view, and are written by authors who probably were that young man not too many years before, so you don't get a very empathetic view towards many fathers. You think of Kafka's father, how he dominates and haunts the Kafka fiction, but you never really get much sense of how the father felt about young Franz.

The father-and-son conflict in Rabbit is Rich just sort of flowed naturally out of "Harry's" aging. He's better with smaller children than with bigger ones. I think with bigger children you need a certain set of principles, something to hang a disciplinary system on, and he doesn't have that system. So with the twenty-two or twenty-three year-old "Nelson," "Harry" is fairly worthless; he just dimly at moments feels sorry for him, but is jealous of his girlfriend, is jealous of his youth, imagines that he enjoys a kind of freedom that he, "Harry", never had, and the rest of it. But maybe by "Nelson's" age a normal boy shouldn't be there in the house with his father. Maybe parenthood has a certain season and curve, and "Harry" has run his curve of fatherhood and feels deep down that he shouldn't have to mess anymore with this child of his. In a way, the position of the father in this conflict is more interesting since it's more ambivalent. There is love along with real animosity. You are both the rival and the protector.

Your interest in genetics is also pretty unusual, I think.

My mother, and her father also, were much interested in family resemblances, and maybe that's what planted this particular theme in my head. One of the things I was trying to show was the power of genes. That is, "Nelson" is in many ways his father's son, but he is also his mother's son, and "Harry is very aware of that, too. He looks at Nelson's hands and sees those little Springer hands. "Nelson" has the misfortune of being the short son of a tall father. The novel, in a way, is a study of inheritance.

By and large, it's not something you find much in novels, do you? Some of Anne Tyler's books attempt to treat families as entities as well as collections of individuals -- Searching For Caleb, for instance. For the younger writers now the nuclear family has become really nuclear. It's you and Mom and maybe Dad, although often he's absent, and you get the feeling of a very narrow focus as far as your own identity goes; whereas in the traditional, stable, small-town setting that I grew up in, you were very aware of your ancestors going back at least to the great-grandfather's generation, and even further, I suppose, if you were an aristocrat.

How does the structure of the novel reflect the action of Rabbit Is Rich?

I think the structure of the novel really hinges on the introduction of strangers into the household. "Nelson" comes home and brings "Melanie", disturbing the little social order there; but then "Melanie" turns out to be just the precursor of "Pru", and her introduction creates a whole new order. The action of the book coincides with "Pru's" pregnancy; that is, all these quarrels and events and conversations are engraved upon the surface of her swelling belly. The book is about the arrival of yet another "Angstrom" -- the little granddaughter who is finally going to compensate for the death of "Harry's" daughter twenty years before. "Harry" is becoming a grandfather, whether he knows it or not, throughout the book. It's a step up, out of the middle range of human experience, into the endgame. When you become a grandparent you're usually the next to go; there's nothing beyond grandparenthood but death, as he senses in the end of the novel.

It's a funny thing: in planning the book, and making this one of the central actions, I kind of thought I would have become a grandfather by that point. But although I had four children, none of them had produced a grandchild, so I had to make it all up. Now I am a grandfather of five, but all boys, and none as old as Judy.

How similar is the real thing to what you imagined?

There's imagination and there's reality, and they're not the same. They're not even in the same ballpark, in a funny way. Although you borrow constantly from real life, in the end what the reader wants, and what you should try to provide, is experience stripped of confusion. Life comes to us full of clutter; every moment is, in a sense, overloaded, and in fiction you try, without totally abandoning that sensation of overload, to hew out actual entities which have shape and flow.

So it might have been less help than you would think to have been a grandparent then. Indeed, it was a help not to have had any of the experiences in this book, really; it is purer that way. "Harry" and I began on the same piece of turf and have much of the same basic equipment as other American Protestant white men, but beyond that we kind of diverged. And yet, if I may say so, for me he continued to live. Each book seems easier when it's over with than it did at the time, but there was a kind of ease always that I associate with the books about "Rabbit". From the title of Rabbit is Rich" on there seemed to be a luxuriance; the details were abundant and coming, and I almost had to stop the book, or it would have gone on forever.

What place does Rabbit is Rich have in your writing life?

It did some nice things for me. After a long period of prizelessness, winning the National Book Award and the other major fiction prizes of the year felt like a step up in my position as an American writer. I felt that not only was I being given a prize, but that a prize was being given to the idea of trying to write a novel about a more-or-less average person in a more-or-less average household. hat vindicated one of my articles of faith since my beginnings as a writer: that mundane daily life in peacetime is interesting enough to serve as the stuff of fiction.

Readers who want learn more abut John Updike are encouraged to seek out some of the books that shaped his writing life:

My Life and Hard Times; Fables for Our Time; The Thurber Carnival, James Thurber Nine Stories, J.D. Salinger Living; Partygoing; Loving; Concluding, Henry Green Remembrance of Things Past, especially Swann's Way and Within A Budding Grove, Marcel Proust

Books by John Updike:

The Afterlife (1994)Brazil (1994) Collected Poems: 1953-1993 (1993) Memories of the Ford Administration (1992) Odd Jobs (1991) Rabbit at Rest (1990) Just Looking (1989) Self-Consciousness (1989) S. (1988) Trust Me (1987) Roger's Version (1986) Facing Nature (1985) The Witches of Eastwick (1984) Hugging the Shore (1983) Bech is Back (1982) Rabbit is Rich (1981) Problems (1979) Too Far to Go (1979) The Coup (1978) The Poorhouse Fair (1977) Tossing and Turning (1977) Marry Me (1976) A Month of Sundays (1975) Picked-Up Pieces (1975) Buchanan Dying (1974) Museums and Women (1972) Rabbit Redux (1971) Bech: A Book (1970) Bottom's Dream (1969) Midpoint (1969) Couples (1968) The Music School (1966) Assorted Prose (1965) A Child's Calendar (1965) Of The Farm (1965) Olinger Stories (1964) The Ring (1964) The Centaur (1963) Telephone Poles (1963) The Magic Flute (1962) Pigeon Feathers (1962) Rabbit Run (1960) The Poorhouse Fair (1959) The Same Door (1959) The Carpentered Hen (1958)

-- Interview by Diane Osen

|

Study the story A&P

You may listen to the story

Comparison of A&P and Araby

Questions to consider

1. Why is the title

of this short story “A & P”? Would another title have worked just as well

or is this

|

one somehow appropriate

to the story? (Setting) What role does the grocery store itself play in the

|

story?

|

2. (Setting) What era

would you place the setting of this story? Does the text indicate any reference

|

to dates? Discuss Sammy’s

description of the year 1990.

|

3. Discuss the way the

language sounds in this story. For example, is it formal or informal? Write

|

down as many of the

slang words that you can identify. What slang words do you think Sammy

|

would use if the A&P

grocery store were located in Saint Leo, Florida and the story was written in

|

2012?

|

4. Talk about the fashions

that the narrator describes in “A&P.” Be ready to read-back to the class

|

any particular lines

that describe the clothing. What do you think that Sammy would consider a

|

“formal” and “informal”

style of dress?

|

5. Discuss the element

of “hypocrisy” in the story. For example, Sammy wonders why it seems okay

|

for the townspeople

to see people in their swimsuits at the beach but not at the market. What

|

other examples of hypocrisy

can you identify in the story? Is there anything about Sammy that

|

comes across as hypocritical?

|

6. In a nutshell, how

would you describe Mr. Lengel? Look in the text for all the clues about him.

|

What are his responsibilities?

What is his role in the community? Would you peg him as a liberal,

|

a moderate, or a conservative?

How do his social politics compare to Sammy’s, for example? What

|

about the other workers

in the store: how are their values like or unlike Mr. Lengel’s?

|

7. How does Updike describe

the other “shoppers” in the market? There are at least six examples; see

|

if you can find them.

What do all of the words that describe the customers have in common? Are

|

they a positive or negative

characterization?

|

8. Look closely at the

dialogue between Stokesie and Sammy after the sixth paragraph of the story.

|

To what, exactly, are

the two gentlemen “reacting”? If this scenario were to take place today, what

|

might the public’s reaction

be? Is this sort of attitude normal? Expected? Perverted? Misogynist?

|

Explore the various

possibilities and be prepared to share with the class.

|

9. Why, exactly, does

Sammy quit his job at the A&P? What, if any, are his reasons? Do you think

|

that Sammy made the

“right” decision to quit?

|

anything?

|

Do you think his “heroic”

gesture changed

|

10. Look closely at

Mr. Lengel’s reaction to Sammy’s resignation. Lengel says that Sammy will

|

“always feel this.”

Sammy agreed with Mr. Lengel. What does that mean? Do you think that

|

Sammy will really

never

forget this? Why or why not? What do you think Sammy will remember

|

[or have learned] from

this incident some years down the road?

|

11. Discuss the relationships

of “POWER” in the short story “A&P.” For example, the relationship of

|

power at the supermarket

itself is that there is a hierarchy of management from those at the very

|

“top” to those at the

very “bottom.” Look at all the characters in the story and decide where their

|

“power” lies within

the scheme of the story. What/who does each character (or set of characters)

|

have power over (their

responsibilities) and who/what has power over them (their superiors)?

|

What power(s) do the

customers have in the A&P?

|

12. It might be said

that “A&P” is something of a modern-day “fairy-tale.” Would you agree with

this

|

assessment? (Stereotype

Characters) Who would the “prince,” the “princess,” the “dragon,” etc. be

|

in “A&P” Be creative

and think of as many analogies as you can. What are the similarities to

|

“A&P” and a typical

fairy-tale? How are they different (for example, the final outcome)? Is

|

Sammy chivalric (means

having the idealistic qualities of a knight in the medieval times of

|

chivalry)?

|

13. (Conflict) Consider

the possibility that Updike might have contrasted the indoor world of the

|

A&P where Sammy

and his co-workers “existed” (synthetic, artificial) with the outdoor world from

|

where the girls came

in (natural). Be creative, but try to point out examples from the text, and

|

show how these two “worlds”

differ. For example, you might think about the fake, fluorescent

|

lights in the store

and the “real” sun outside that can give someone “sunburn.” Like Plato’s

|

“Allegory of the Cave,”

is there a difference/contrast between the world “inside” the A&P and the

|

outside world?

|

14. In Literature, a

work like “A&P” is called a “coming-of-age” story. It usually suggests a loss

of

|

innocence or an “epiphany”

that leads to maturity. Sometimes this means accepting responsibility

|

(and becoming more like

an adult). Think back on either books or films that you have experienced

|

either in or out of

this class that might have the “coming-of-age” theme. Make a list and share it

|

with the class, e.g.,

Pretty

in Pink, Stand by Me, Stealing Beauty, etc. Finally, consider

the

|

protagonist of “A&P”

and the “change” that occurs in his character; decide why a label like

|

Study Questions for John Updike’s “A&P” |

1. Notice how artfully Updike

arranges details to set the story in a perfectly ordinary

supermarket. What details stand out for you

as particularly true to life? What does this

close attention to detail contribute to the

story?

2. How fully does Updike draw

the character of Sammy? What traits (admirable or

otherwise) does Sammy show? Is he any less

a hero for wanting the girls to notice his

heroism?

3. Exposition is usually the

opening portion of a narrative. In the exposition, the scene is

set, the protagonist is introduced, and the

author discloses any other background

information necessary to allow the reader to

understand and relate to the events that

are to follow. What part of the story seems

like the exposition?

4. As the story develops, do

you detect any change in Sammy’s feelings toward the girls?

5. Where in “A&P” does the

dramatic conflict become apparent? What moment in the

story brings the crisis? What is the climax

of the story?

6. Why, exactly, does Sammy

quit his job?

7. Does anything lead you to

expect Sammy to make some gesture of sympathy for the

three girls? What incident earlier in the story

(before Sammy quits) seems a

foreshadowing?

8. What do you understand from

the conclusion of the story? What does Sammy mean

when he acknowledges “how hard the world was

going to be . . . hereafter”?

9. What comment does Updike—through

Sammy—make on supermarket society?

|

Comments

Post a Comment