William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) The Second Coming

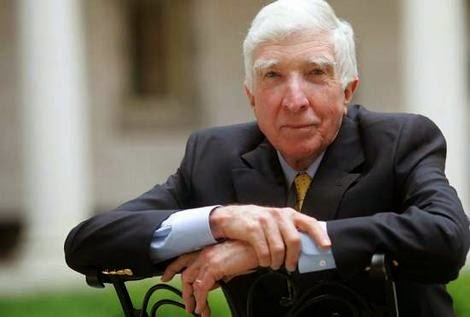

William Butler Yeats

(1865-1939)

Born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1865, William Butler Yeats was the son of a well-known Irish painter, John Butler Yeats. He spent his childhood in County Sligo, where his parents were raised, and in London. He returned to Dublin at the age of fifteen to continue his education and study painting, but quickly discovered he preferred poetry. Born into the Anglo-Irish landowning class, Yeats became involved with the Celtic Revival, a movement against the cultural influences of English rule in Ireland during the Victorian period, which sought to promote the spirit of Ireland's native heritage. Though Yeats never learned Gaelic himself, his writing at the turn of the century drew extensively from sources in Irish mythology and folklore. Also a potent influence on his poetry was the Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne, whom he met in 1889, a woman equally famous for her passionate nationalist politics and her beauty. Though she married another man in 1903 and grew apart from Yeats (and Yeats himself was eventually married to another woman, Georgie Hyde Lees), she remained a powerful figure in his poetry.

Yeats was deeply involved in politics in Ireland, and in the twenties, despite Irish independence from England, his verse reflected a pessimism about the political situation in his country and the rest of Europe, paralleling the increasing conservativism of his American counterparts in London, T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. His work after 1910 was strongly influenced by Pound, becoming more modern in its concision and imagery, but Yeats never abandoned his strict adherence to traditional verse forms. He had a life-long interest in mysticism and the occult, which was off-putting to some readers, but he remained uninhibited in advancing his idiosyncratic philosophy, and his poetry continued to grow stronger as he grew older. Appointed a senator of the Irish Free State in 1922, he is remembered as an important cultural leader, as a major playwright (he was one of the founders of the famous Abbey Theatre in Dublin), and as one of the very greatest poets—in any language—of the century. W. B. Yeats was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1923 and died in 1939 at the age of 73.

The Second Coming

Listen to the poem:

Listen to the lecture about the poem:

Study Guide

Discussion Questions

Bring on the tough stuff - there’s not just one right answer.

- Why do you think Yeats put so many confusing symbols in the poem? Many poets, when they use symbolism, try to make everything relate to each other. But what does falconing have to do with a sphinx or a "blood-dimmed tide," and what does either of them have to do with a sphinx and the "indignant desert birds"? Most people who read this poem want to make these things correspond to something real in the world. But we have to consider that Yeats did not want his poem to be interpreted in this way.

- How would you explain the poem’s relationship to the Bible? Most of the symbols are very general and timeless, like something out of the Book of Revelation. But it’s also easy to tell that this is notthe Bible. For one thing, Christ doesn’t show up at the end, but a "rough beast." Does the poet sound like a religious man, and, if so, what kind?

- Why does Yeats think of history as this swirling vortex, the gyre? Because the gyre moves further and further from its center, does it mean that things are always getting worse? It should be mentioned that Yeats’s idea was highly original and not shared by everyone. There are still plenty of people, even today, who think that history is linear (except for a few blips like wars), and that society is constantly improving itself.

- Is it possible that the appearance of the "rough beast" could be good for the world, in the end? After all, if the world is already so violent that "innocence is drowned," things can’t get much direr. Maybe Yeats thinks it’s like tearing down an old building in order to put up a new one. But, then again, there’s nothing in the poem about society rebuilding itself.

- Do you think the poem could apply to the entire world, or is it only intended for Christian Europe? People in other civilizations, for example the Middle East, have found this to be a very compelling poem, and they have made it fit into their own views of history. Maybe it speaks most directly to people with an "apocalyptic" outlook, who think that big, sweeping changes are on the horizon.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment